Our Mission

The Regional Cooperation Council serves regional cooperation and Euro-Atlantic integration of South East Europe, in order to spark development in the region to the benefit of its people

Results / Outputs

Did you know?

What we do

Helping prosperity and growth through regional action in South East Europe, while supporting European and Euro-Atlantic integration, is what the Regional Cooperation Council is all about. We see our region as a place of dialogue, freedom and mobility, rich in cultural heritage, where each person feels safe and protected by the rule of law.

Digital Transformation

Connecting the region

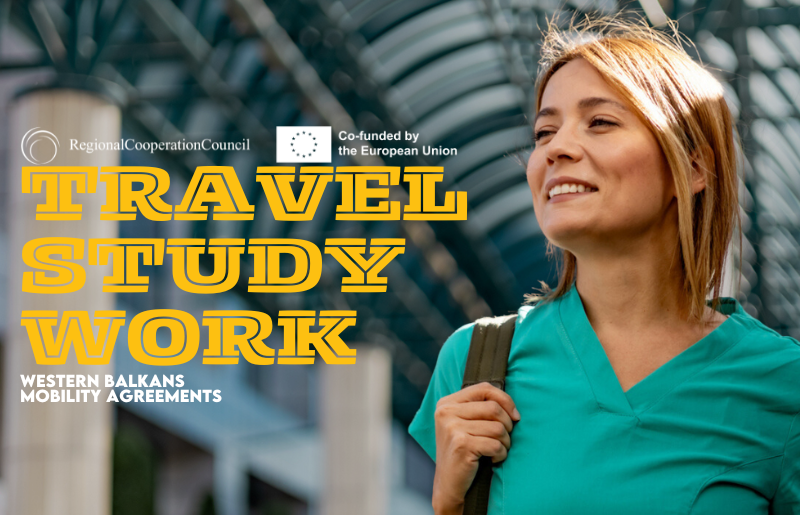

Human Capital

Unlocking the potential

Green Agenda

Greening the future

Competitiveness

Lifting economy barriers

Security Cooperation

Towards safe and secure region

Regional Coordination

Driving collaborative progress in South East Europe